Why Japanese people don't do 'ikehana'

The phonology of Japanese has always felt tidy to me. There’s a small set of phonemes - around 20. Syllables are generally CV (consonant vowel) or CVV1. It’s a moraic language. Simple. Recently though, there’s been a nagging question in the back of my mind.

In environments where voiceless obstruents become voiced, why does [h] change to [b]? In fact, why does it change at all?

The following is a discussion of how I found out. It begins with a exploration of rendaku (voicing assimilation in compound words) and ends by looking at a series of historical sound changes in Japanese and how these have given us this funny looking rule. So, time to spell out the problem a little more clearly.

What’s the deal with rendaku?

Rendaku, or sequential voicing, describes a phenomenon in Japanese where voiceless obstruents in compound words become voiced following a vowel in the preceding morpheme. For example:

声 koe [koe] ‘voice’

becomes:

大声 ōgoe [oːgoe] ‘big voice/loud voice’

(Note - the format for the examples throughout this section is as follows: kanji, romanized transcription (romaji), IPA transcription, translation)

Learners of Japanese are taught about this phenomenon fairly early in their studies. There are plenty of exceptions (e.g. Lyman’s Law), though at least the phenomenon itself is fairly intuitive, i.e. voicing assimilation sometimes occurs in compound words. Bucking this intuitive trend, however, are examples involving /h/-initial syllables in Japanese. In romaji these syllables are written as “ha, hi, fu, he, ho”. Let’s just look at the first three syllables (“ha, hi, fu”), which are realised as [ha], [çi] and [ɸɯ] respectively, and see what happens post-rendaku.

(1) 花 hana [hana] ‘flower’ + 火 hi [çi] ‘fire’ = 花火 hanabi [hanabi] ‘firework’

And now compare that with it’s mirror image in (2):

(2) 火花 hibana [çibana] ‘spark’

And then with:

(3) 勝 shō [ʃoː] ‘win’ + 負 fu [ɸɯ] ‘lose’ = 勝負 [ʃoːbɯ] ‘victory or defeat, match’

So, there are three allophones of /h/ here: [ç], [h] and [ɸ]. All of these become /b/ in cases of rendaku. Weird.

When I first came across words like this (and it doesn’t long), I’d assumed there had been some obscure sound change in the past and that what we had today was a funny looking remnant of Old Japanese, or Middle Japanese, or some other antiquated version of the language I don’t understand. Something you could explain in a neat little phonological rule.

Turns out I was half-right. The change did begin hundreds of years ago. However, it’s actually the result of a series of sound changes. No single, straightforward rule here. So, what’s going on?

From Point A to Point [bi]

To get started, I went straight to Kubozono’s (2015) Handbook of Japanese Phonetics and Phonology.

The first reference to the /h/ getting up to funny business is in the introduction. As it turns out, /p/ > /h/ is a historical change and artifacts of this change crop up in Modern Japanese in all sorts of interesting ways. /h/ > /b/ during rendaku is one. But equally as interesting is /p/ being preserved in onomatopoeiac words. For example, ‘light’ has undergone the sound change, whereas pikari ‘the sound lightning makes’ has not. It’s also behind the alternation in nihon and nippon ‘Japan.’

Huh, I thought. Who would have guessed?

But learning this immediately raised the question of how this sound change happened. After all, I thought to myself, [p] doesn’t sound anything like [h]. They’re produced about as far away from each other in the mouth as physically possible. So, I went after the name of this mysterious sound change.

‘Spirantization’ and other words I didn’t know until recently

Moving from the voiceless stop [p] to the more open glottal fricative [h] is an example of weakening, that is, consonants becoming more vowel-like. Another name for this process is ‘lenition,’ depending on how pretentious you’re feeling.

Naturally then, the Wikipedia page on lenition provided me with my answer.

Three processes are involved in turning /p/ to /h/:

- affrication (i.e. sticking a fricative in there): /p/ > /pɸ/

- spirantization (i.e. turning an affricate into a plain old fricative) /pɸ/ > /ɸ/

- debuccalization2 (i.e. shifting a consonant’s place of articulation to the glottis) /ɸ/ > /h/

So, although long-winded, the sound change is attested.

Pulling it all together

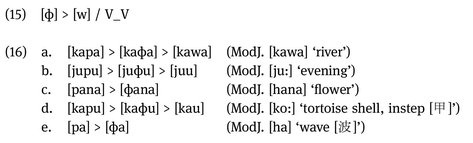

Returning to the Handbook of Japanese Phonetics and Phonology, I found a neat little illustration of the above sound changes in Chapter 15, “Historical phonology,” by Takayama (2015).

Okay, this will take a little unpacking. As discussed in the previous section, at some point there must have been a sound change from [p] > [ɸ]. All instances of the stop [p] became the fricative [ɸ]. After this, however, another sound change took place in Japanese. This can be seen in (15) above - [ɸ] becomes [w] intervocalically.

In (16)c and (16)e, both words which begin with [ɸ], there is no vowel preceding [ɸ], so there is no change to [w]. Instead, the sound at the beginning of these words eventually undergoes debuccalization (see above) and gives us the modern day [hana] ‘flower’ and [ha] ‘wave.’

Elsewhere though, [ɸ] > [w] proceeded as described in (15) [kawa], except when the second vowel was /u/. Here, a further rule comes into play. Because /wu/ was phonotactically illegal at the time of the change, the intervening consonant [w] was elided, producing (16)b and (16)d.

And there you have it - a neat little sound change in (reconstructed) action. As we can see, /p/ has been getting up to all sorts of antics in Japanese for hundreds of years.

Conclusion

So, to return the original question: why does [h] become [b] in environments which trigger voicing? The answer is that /p/ has undergone a series of sound changes in Japanese, roughly, [p] > [ɸ] > [h], to become modern day /h/. The mysterious [b] in rendaku is an artifact of the Old Japanese pronunciation [p].

Additional sound changes in the language, and the long list of exceptions to rendaku, have made the origins of [h] to [b] pretty opaque. Hopefully, the summary provided here makes things a little clearer for those equally puzzled by this quirk of Modern Japanese.

References

Kubozono, H. (Ed.). (2015). The handbook of Japanese phonetics and phonology (Vol. 2). Boston: Walter de Gruyter.

Lenition. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved 28 May, 2018, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lenition

Takayama, T. (2015). Historical phonology. In H. Kubozono (Ed.), The handbook of Japanese phonetics and phonology (Vol. 2). Boston: Walter de Gruyter.

Further reading

For a general outline of rendaku the Wikipedia entry is a great start.

If you’ve had some experience learning Japanese and can read hiragana, Tofugu have a nice rendaku explainer with plenty of examples.