Fly me to the /ksks/: A brief look at Southern Ryūkyūan phonology

Ever since hearing Madoka Hammine talk about the Southern Ryūkyūan language of Yaeyama on the excellent Field Notes podcast, I’ve had a hankering to learn more about this language family.

What I’ve discovered over the past couple of weeks has been fascinating. So I couldn’t help but share some interesting snippets.

A quick sketch of the social context

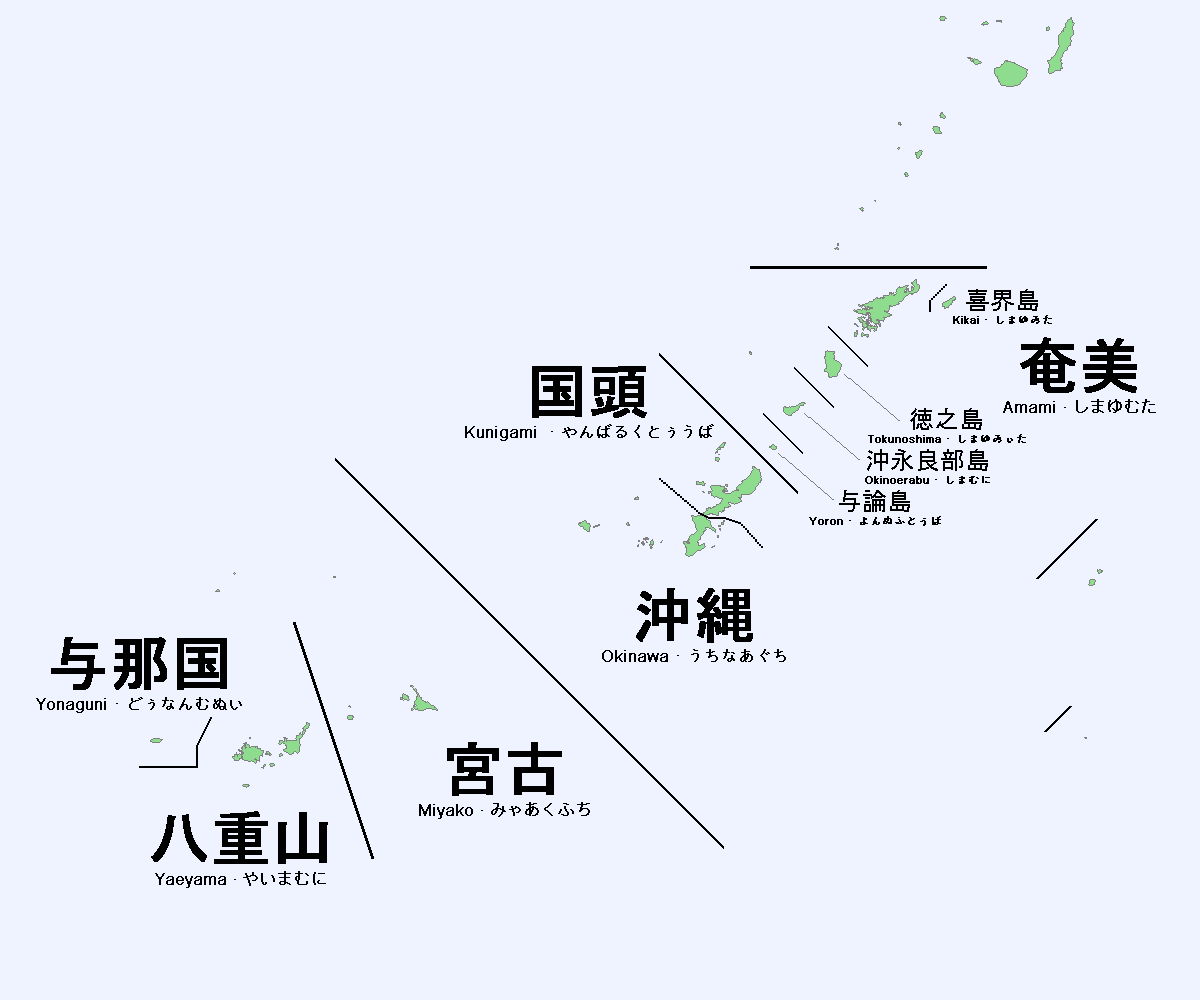

An overview of the languages spoken in the Ryūkyū islands. Image by Garam.

An overview of the languages spoken in the Ryūkyū islands. Image by Garam.

Ryūkyūan languages descend from Proto-Ryūkyūan, a sister language of Japanese. It’s thought that the linguistic split from Proto-Japanese occurred in the first few centuries CE, and that Proto-Ryūkyūan was then spoken on the Japanese mainland for several centuries before migration to the Ryūkyū islands.

Large-scale migration to the Ryūkyū islands from Japan probably occurred around 1000 years ago, with the Japanese settlers completely displacing the pre-existing population. A detailed discussion of prevailing theories of migration can be found in Pellard (2015).

Ryūkyūan languages are not mutually intelligible with Japanese. Moreover, there’s very limited intelligibility between Ryūkyūan varieties (more on this soon). Despite this, the Japanese government considers all Ryūkyūan languages to be dialects of Japanese.

As noted by Shimoji (2010: 2), although the population of the Ryūkyū islands is roughly 1.5 million, almost all speakers of Ryūkyūan languages are now over 60, so total speaker numbers are likely to be small. Exact figures are unknown. The younger generations are, universally, monolingual Japanese-speakers.

The languages

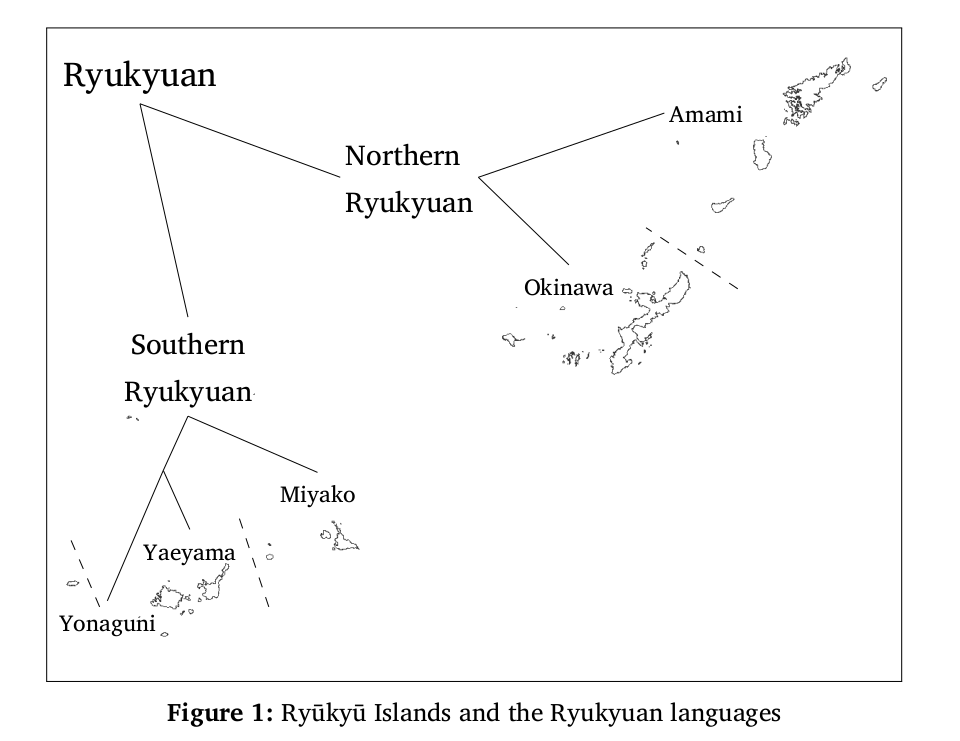

Things get a little messy here. Deciding what constitutes a unique language is always a difficult task. Mutual (un)intelligibility is often a useful yardstick for the language/dialect distinction. So although the are a great many language varieties spoken in the Ryūkyū islands, five major languages have been identified. These differ so much from one another that speakers of one language (or variety within it) would not understand speakers of another. From north to south the languages are: Amami, Okinawan, Miyako, Yaeyama, Dunan (Yonaguni). The greatest divergence can be seen between the northern and southern languages.

As can be seen in the map below, taken from Shimoji (2010: 3), geography seems to have played a role in this split. The greatest uninterrupted distance between any two island groups is that separating the north and south.

Phonology

On to the juicy bits!

Really there’s so much to unpack here that I’ll have to stick to some select highlights.

Echoes from the past

Since Ryūkyūan forms a sister branch of languages with Japanese, it’s interesting to compare the two and see which Proto-Japanese features have been preserved in Ryūkyūan but not Japanese.

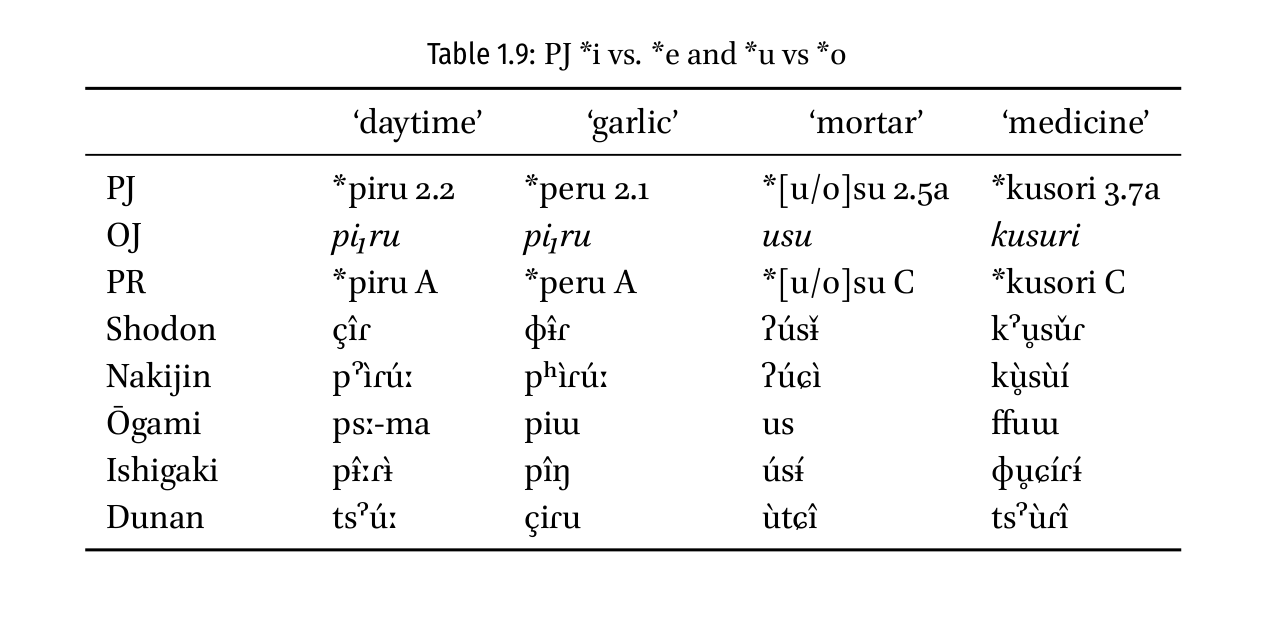

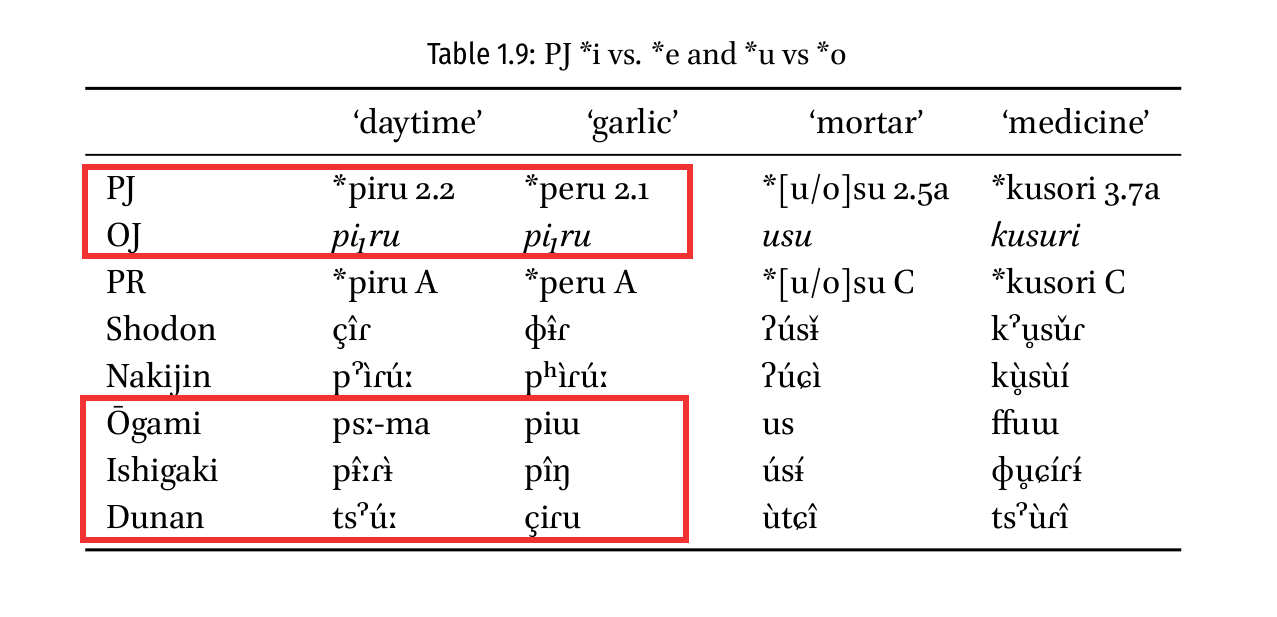

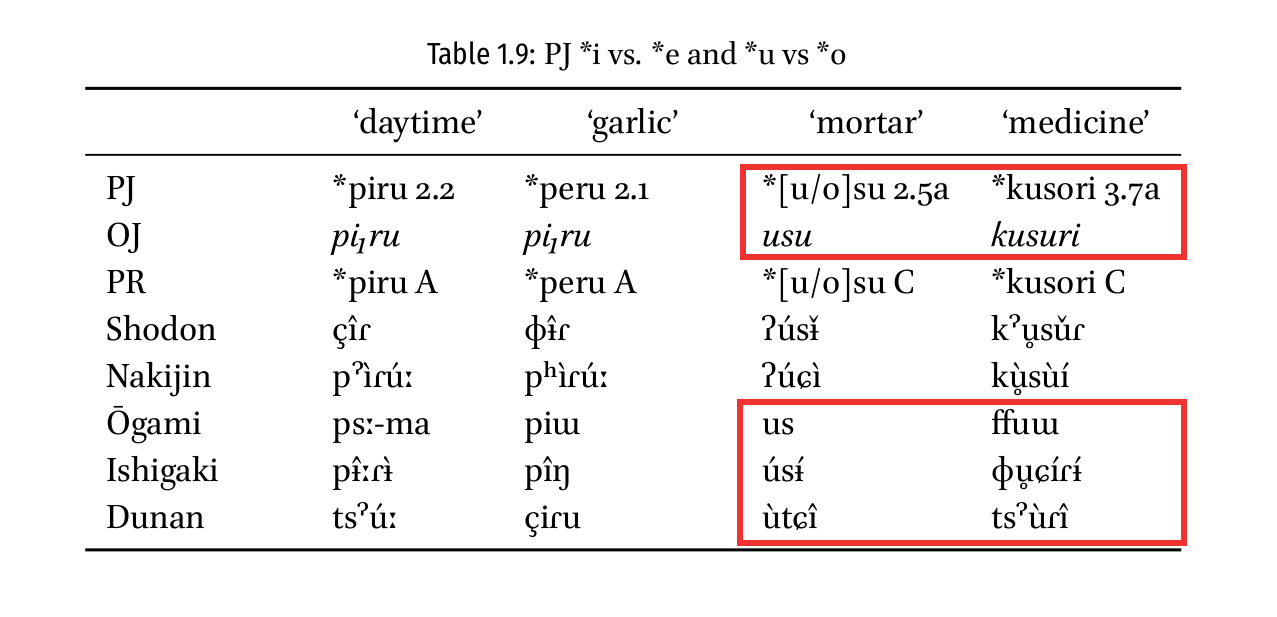

For example, Ryūkyūan languages still display phonological distinctions that began to disappear in Old Japanese (8th century CE). Whereas in certain environments OJ started merging *i with *e and *o with *u, Proto-Ryūkyūan kept these distinctions, which still exist in the present day languages. Pellard (2015: 22) illustrates this phenomenon in the table below.

Looking more closely at the first to columns, the Proto-Japanese words for ‘daytime’ (/piru/) and ‘garlic’ (/peru/) are not homophones. However, in Old Japanese they are.1 Ryūkyūan languages, on the other hand, distinguish these words in some way. I’ve highlighted the Southern Ryūkyūan languages, as that’s the topic of this post, though the distinction is preserved in the northern varieties too.

Ignoring the other vowel/consonantal shifts which have also taken place, it’s clear that there remains a systematic difference between the first syllable of the words for ‘daytime’ and ‘garlic.’

Compare:

- Ōgami /psː/ vs. /pi/

- Ishigaki /pɨ/ vs. /pi/

- Dunan /tsˀ/ vs. /çi/2

Similarly, the Proto-Japanese *u and *o remain unmerged in Ryūkyūan too.

Syllabic fricatives!

“That’s a thing‽”

Oh, you betcha.

Ōgami and Irabu, which both fall under Miyako Ryūkyūan, illustrate this particularly nicely. In these languages fricatives like /ʋ/ can both form the nucleus of a syllable. Nasals can too.

Pellard (2010: 119) provides the following examples in Ōgami.

- /mm/ [m̩ː] ‘yam’

- /ʋʋ/ [v̩ː] ‘sell’

- /ntɑ/ [n̩tɑ] ‘where?’

- /pstu/ [ps̩tu] ‘person’

- /ftɑi/ [f̩tɑi] ‘forehead’

- /ksks/ [ks̩ks̩] ‘moon’

In Irabu the retroflex lateral approximant /ɭ/ is also a possible nucleus (Shimoji 2008: 45).

- /prr.ma/ [pɭːma] ‘daytime’

- /na.brr/ [nabɭː] ‘slippery’

This is – I mean – wow. I love just how distinctive these languages sound. It’s not even as if these syllabic fricatives/nasals/approximants are found only in low frequency vocabulary items. They’re everywhere! I didn’t even know there were languages like these.

Oh, and it gets better.

Both vowel and consonantal length is distinctive in Southern Ryūkyūan. And while the same is also true in Japanese, where geminate consonants are distinctive (e.g. kita ‘came’ vs. kitta ‘sliced’), Ryūkyūan takes it to another level. Consider the following (Pellard 2010: 118).

- /fɑɑ/ [fɑː] ‘child’

- /f.fɑ/ [fːɑ] ‘grass’

- /ff.fɑ/ [fːːɑ] ‘comb=ᴛᴏᴘ’

Each word contains the same two phonemes, but they’re all differentiated by the segments that are lengthened. I’ve never seen that triangular colon do so much work! Again, this absolutely blows my mind.

Conclusion

All in all, stumbling across this language family has been an absolute delight. The brief sketch of the languages I’ve provided has really only scratched the surface. I’d love to dig deeper in future posts. Hopefully I don’t fall too far down the rabbit hole. I hear it’s a [nabɭː] slope.

References

Shimoji, Michinori. 2008. A grammar of Irabu, a Southern Ryukyuan language. Canberra: Australian National University. (Doctoral dissertation.)

Shimoji, Michinori. 2010. Ryukyuan languages: an introduction. In Shimoji Michinori and Thomas Pellard (eds.), An Introduction to Ryukyuan Languages, 113–166. Tokyo: Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa.

Pellard, Thomas. 2010. Ōgami (Miyako Ryukyuan). In Shimoji Michinori and Thomas Pellard (eds.), An Introduction to Ryukyuan Languages, 113–166. Tokyo: Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa.

Pellard, Thomas, 2015. The linguistic archeology of the Ryukyu Islands. In Patrick Heinrich, Shinsho & Michinori Shimoji (eds.), Handbook of the Ryukyuan languages: History, structure, and use, 13-37. Berlin; Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

-

As is also the case in Modern Japanese 昼 hiru ‘daytime/noon’ and 蒜 hiru ‘garlic’ (uncommon). ↩︎

-

I’m assuming /tsˀ/ is being used syllabically here, though that could be wrong – the vowel may have undergone epenthesis – making the word monosyllabic. In either case, the phonological distinction between the words being compared is clear. ↩︎