Character building: a review of kanji learning web app WaniKani

Today, I’m going to give my thoughts on the kanji learning web app Wanikani.

I came to Japan just under year ago with next to no Japanese. I knew a few phrases and could haltingly sound out hiragana and katakana, but not much else. Since then, I’ve tried a range of methods to learn the language - textbooks, apps, private tutoring, websites, watching local TV shows. You name it, I’ve probably either tried it or am still doing it. One of the things I’ve stuck with most consistently is Wanikani.

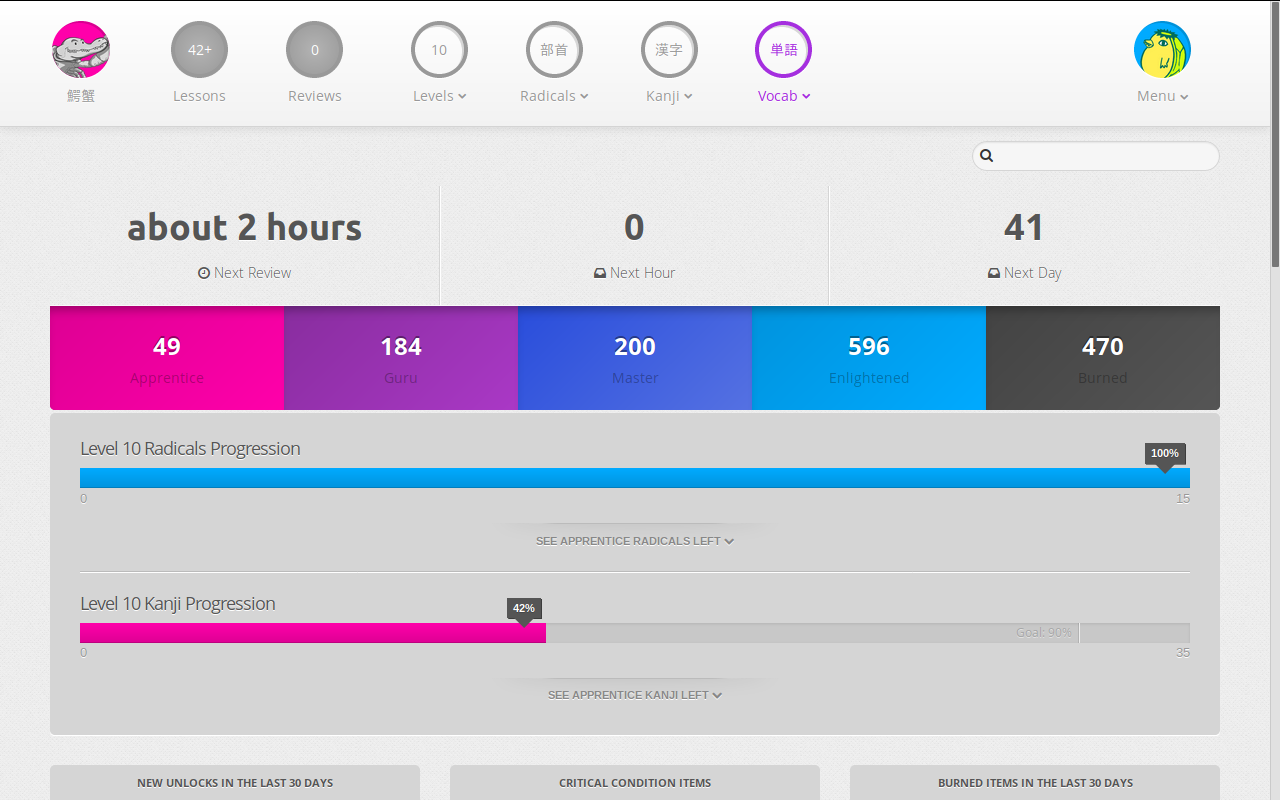

A snapshot of a review session on WaniKani

A snapshot of a review session on WaniKani

How it works

Wanikani is a web app for learning kanji and vocabulary. Using a spaced repetition system, new items are gradually introduced to the user and then tested at increasing intervals. Basically, it’s an shiny looking, full-featured flash card application.

The process of learning new items goes roughly like this:

- Learn the names a small set of radicals, the little graphical building blocks of Chinese characters. (Names of radicals vary between indexing systems. Wanikani sometimes uses it own labels, e.g. “Boobs,” “Wolverine” and “Sauron,” rather than the more traditional ones.)

- Learn the meanings and readings of kanji composed of known radicals

- Learn a set of vocabulary items (i.e. words containing one or more kanji)

- Repeat

In order to learn a new kanji, Wanikani provides a mnemonic - a story about the radicals that make it up. This story is then extended to help you learn one of the readings for the kanji. Normally, the first reading learnt is the on’yomi (a reading based on the original Chinese one), while alternative on’yomi and kun’yomi (native Japanese readings) are introduced later with new vocabulary items.

Audio recordings of new vocabulary items are baked in. When new kanji are being learned, the user is shown several vocabulary items containing the kanji. When new vocabulary items are being learned, the user is given a set of example sentences. Rad.

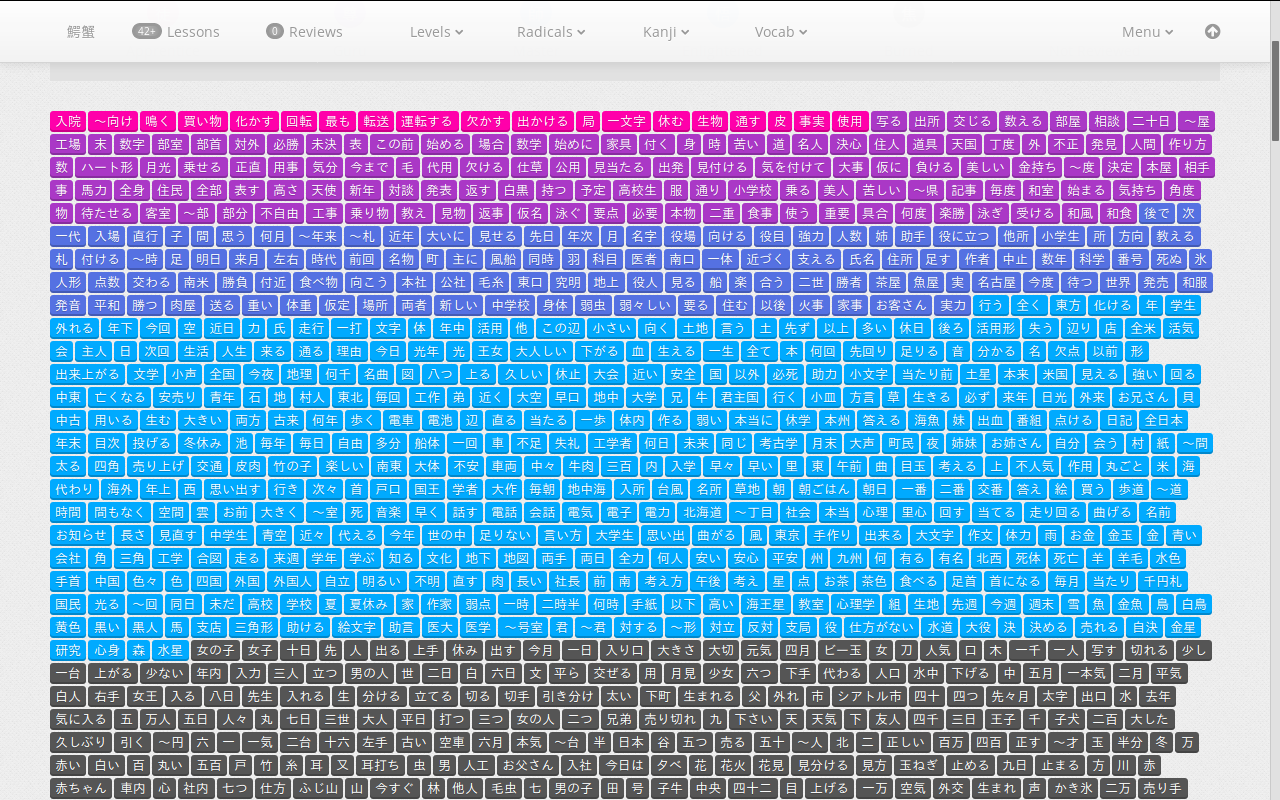

By learning new items and reviewing past items, users advance through Wanikani’s 60 levels. There are around 2000 kanji and 6000 vocabulary items to learn. According to Wanikani, both these mammoth lists can be learnt in just over a year.

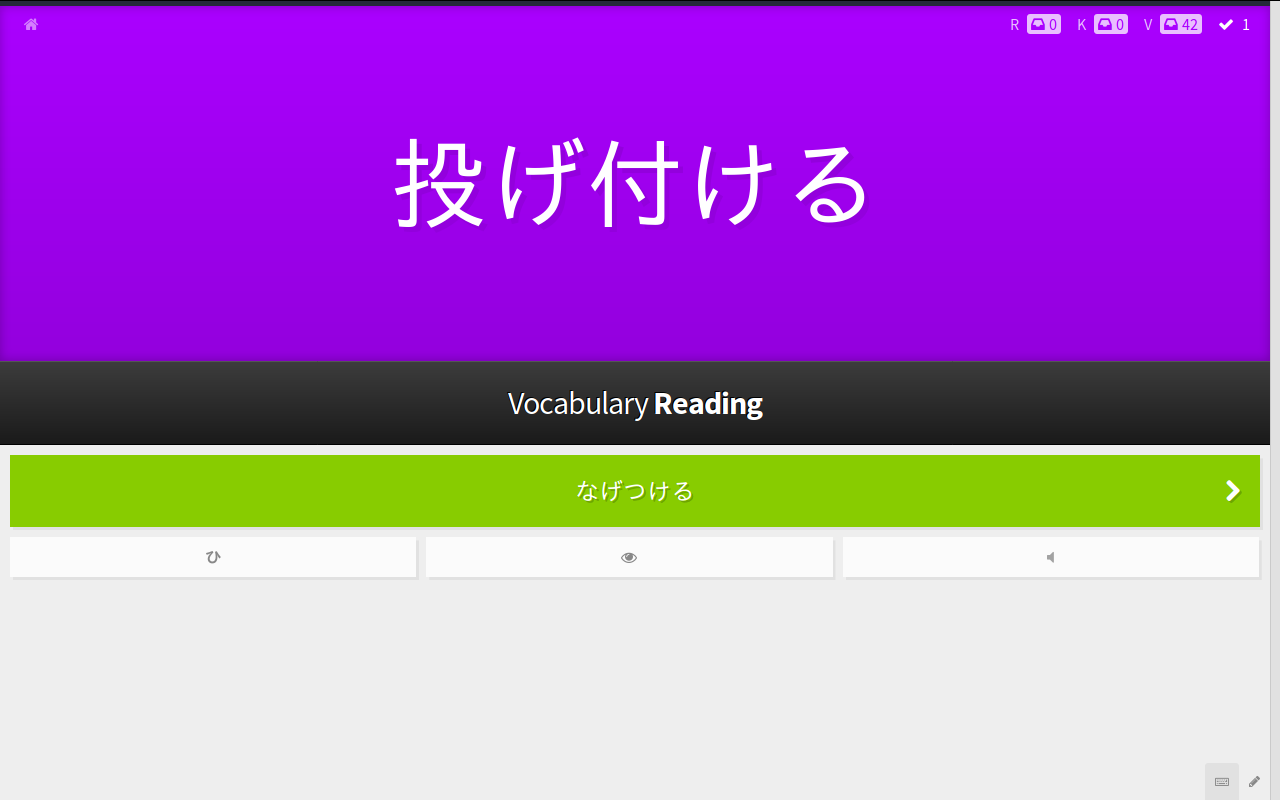

The site is registration based, though users can access the first three levels for free. Given how much work has clearly gone into this project, I don’t think pricing structure is unreasonable. Personally, I find having paid for a service makes me much more inclined to use it regularly.

My only gripe here would be that you can only see the different subscription options once you’ve created an account. In fact, it’s only by scrolling to the very bottom of the homepage that you can even see it’s a paid service (“How many kanji can you learn this month? Try WaniKani for free”).

Update 27/12/18: The WaniKani FAQ section has been updated. You can now find the pricing options (without creating an account) here .

A look at WaniKani’s three pricing options

A look at WaniKani’s three pricing options

What I like

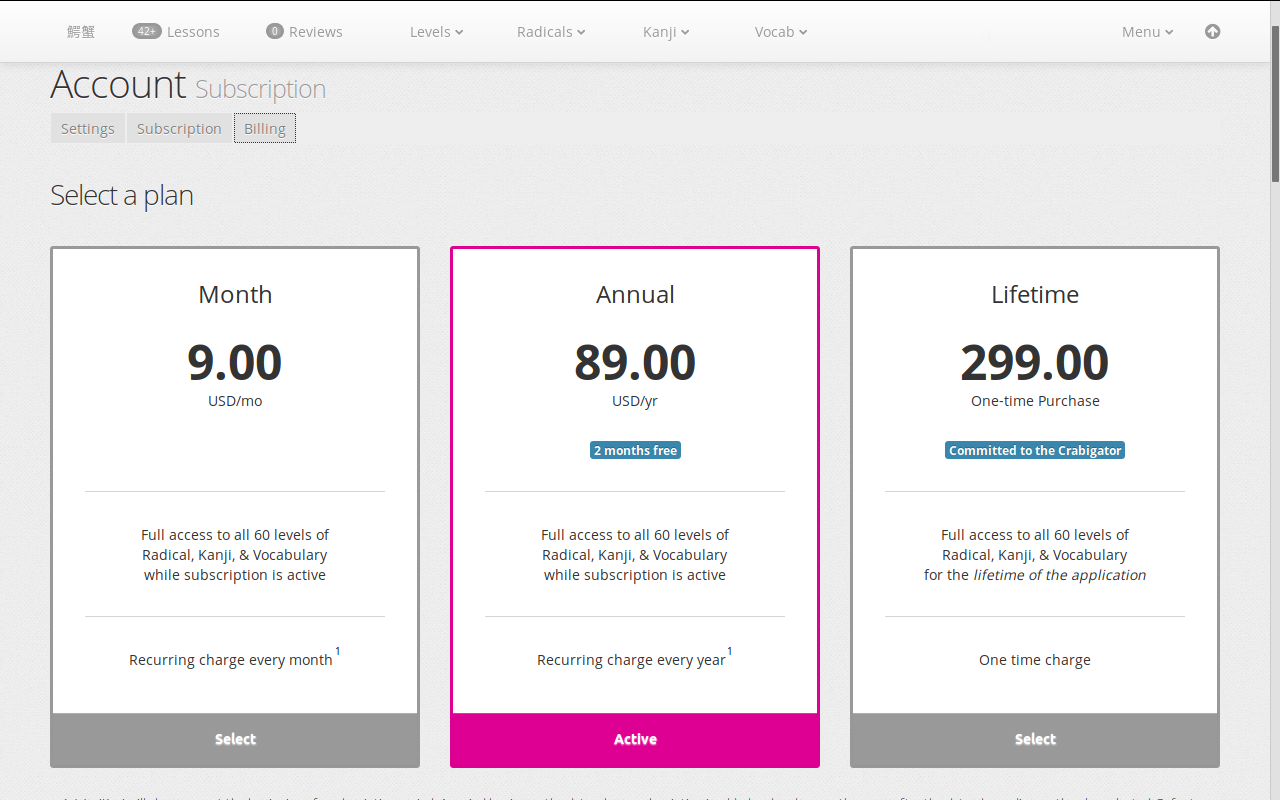

Wanikani is polished. Really polished. The user interface is simple and visually appealing. Same goes for their Android and iOS versions. Like just about every other language learning app out there, a lot of work has been put into gamifying the otherwise mundane task of memorizing wordlists. Fluorescent bars inform you of how far through a level you are. A few clicks takes you to a brightly coloured list of each kanji/vocab item you’ve learnt. It’s intuitive and nice to use.

A view of my vocab progress - different colours represent how well each item is known

A view of my vocab progress - different colours represent how well each item is known

Nevertheless, Wanikani hasn’t gone too far down the let’s-make-learning-as-close-to-video-games as possible path. You don’t earn points. You don’t unlock trophies or awards. There are no cheesy sounds that play when you complete a level. You’re there to learn vocab. And since you’ve already paid your subscription fee, there’s no incentive for Wanikani to try and squeeze every last minute/dollar out of you by getting you slavishly addicted. Sure, the experience encourages you to come back, but I suspect for most people it’s a matter of wanting to, not needing to.

Secondly, the system of mnemonics is nicely put together. Each kanji/vocab item’s backstory is as bizarre, entertaining and memorable as you’d want it to be. Importantly, the stories often build on each other, reducing the memorization burden. Granted, you’ll still forget most of these anecdotes in short order, but when you’re trying to recall the meaning/reading of a kanji the first few times they’re surprisingly effective. These are a real asset to the app and something that separates it from its competitors.

More good bits

As mentioned earlier, once users have learnt a new kanji’s meaning, they then learn a small set of vocabulary items which contain it. This has the benefit of teaching nuances in the character’s meaning and contextualizing the new knowledge. For example, a user learns 転 ten ‘revolve,’ shortly before learning 回転 kaiten ‘rotation’ (as in kaitenzushi, conveyor belt sushi) and 自転車 jitensha ‘bicycle’ (lit. self revolving vehicle). The choice of vocabulary items is key here. Choose a set of items that are too semantically similar and you end up with interference. I’ll come back to this later. For now, I’ll say that I’m glad Wanikani have applied this meaning-rich approach to vocabulary learning and that it’s lead to plenty of “Aha!” moments for me.

Lastly, a number of other sites (e.g. KaniWani and Bunpro) have Wanikani integration through the Wanikani public API (application programming interface). This means that your current level of vocab knowledge can be used to tailor other web apps for you. A full list of userscripts and third-party apps using the public API can be found here if you’re curious. Personally, I don’t have any experience with these beyond KaniWani and Bunpro.

Mnemonics for mnemonics?

As much as I’m impressed by the sheer creativity and entertainment value of the mnemonics Wanikani has created, sometimes they just fall flat. For complex kanji, this can simply be because the story is too long. Remembering what Sauron did with the pair of boobs in the car during winter1 can be harder than simply rote-learning a meaning and reading.

Another problem I have with the mnemonics is that they sometimes play on some aspect of American English pronunciation. Being a New Zealand English speaker means that “cot” and “caught” aren’t homophones or even near homophones for me. Nor is my variety of English rhotic, which again impedes some mnemonics’ effectiveness. For the most part, this an issue, though there have been some items I’ve struggled to get my head around because the mnemonic worked best in American English.

It should be said that users can come up with their own mnemonics if those provided don’t help. Nevertheless, you are paying quite a bit for Wanikani’s mnemonic system, so I feel these criticisms are not unfairly nitpicky.

Semantic clustering

Earlier, I noted how much I liked learning the nuanced meanings of kanji by seeing them in different vocabulary items. This is really cool. If not done carefully, however, introducing lots of vocabulary around a certain theme (or morpheme) can be a burden for the learner.

Many textbooks and language courses teach vocabulary in ‘lexical sets’ - different kinds of fruit, for example. It’s normal for parts of the body to be taught at the same time. This is known as ‘semantic clustering’ in second language acquisition research. Turns out, although seeming like a good idea on paper, it can really slow down acquisition of vocabulary. Nation (2000) provides a nice summary of the research on this topic. You can find the pdf version here. One of the takeaways is that teaching similar vocabulary or near synonyms at the same time is generally not a good idea.

Overall, WaniKani doesn’t do too badly on this score. To it’s credit, when you learn a new kanji, you aren’t then taught every single word it features in. Eventually though, you will come across semantically similar words and have to distinguish betweeen them.

To illustrate, let’s look at how the kanji for ‘mix’ 交 is handled. When you learn this, you also learn the verb ‘to mix something’ 交ぜる. Perfectly reasonable. Three levels later you learn the verbs ‘to be mixed’ and ‘to intersect,’ both of which contain 交. These words are, understandably, easily confused. But what makes things doubly difficult is when you get one or both of these wrong in a review. Once this happens they start cropping up more frequently in future reviews, often near each other. Amongst all this, the original 交ぜる might then raise it’s head again. And if you get this wrong, things really snowball. You’re confronted with three semantically similar items which you now have to consistently distinguish between without context.

Essentially, the problem arises when you learn similar items and then get one (or more) wrong in a review. Even if these have been introduced at different levels, the spaced repetition system gives preference to recent mistakes and will start putting them near each other, exacerbating the confusion.

WaniKani has mitigated the problem somewhat by spreading out items like these when you’re learning them. Unfortunately, the review system isn’t so careful.

Wait, how fast did you say I’d learn these kanji?

WaniKani’s home page makes the claim that you can learn 2000 kanji and 6000 vocabulary words in “just over a year.” Bold. Personally, after using the app for nine months I’m only at level 10. By my own admission I’ve been taking things slowly, but still. 2000 kanji in that time?

As it turns out, WaniKani’s FAQ qualifies their claim:

It will depend on your pace. Some people can complete the main levels (1-50) in about a year. But that’s really, really fast. One and a half years is a very reasonable “fast” speed to complete all of the content up to level 60. Then add at least six more months to “burn” every single item after reaching level 60.

Speed will depend on how quickly you do the items in your lesson queue, how often you do your reviews (once or twice a day is what we recommend), and how many correct/incorrect answers you’re giving. But, compared to traditional methods, we bet you’ll notice results to be both easier and much faster.

So, unless you’re really pushing it, it’s probably going to take you a minimum of a year and a half to get through the content. Two years seems like a much more reasonable target for those who have lives outside of kanji study (*gasp*). Then an additional 6+ months to really solidify that knowledge.

The initial claim, therefore, is a little cheeky, but not as drastic as it first seems.

What I cannot understand is why the FAQ and About sections explaining this are available only to registered users. Previously, I mentioned how I didn’t like needing an account to view the pricing structure. Well, turns out you need an account to access any of the site’s resources at all, even to find out what kind of service you’re signing up for.

I just. Why? You shouldn’t have to go to a third-party (me in this case) to find out the basic features of an app. Simple. This information should be available to anyone.

Update 27/12/18: Account registration is no longer required to view the FAQ! All relevant info can now be found at https://knowledge.wanikani.com. However, I’m still really disappointed a link to the FAQ isn’t provided on their landing page. How is anyone considering signing up ever going to find this?

Different strokes for different folks

What is the optimal order for learning kanji? Should the first kanji you learn be the highest frequency items or those of the lowest complexity (stroke count)? Is there a happy inbetween?

Starting out, WaniKani users learn very simple radicals. Then, they learn very simple kanji, e.g. ichi 一 ‘one.’ Gradually, the number and complexity of the radicals and kanji increases. The nice thing about this approach is that you aren’t bombarded with intimidating looking kanji right from the outset, just because they’re common. From personal experience, seeing words like 曜日 yōbi ‘day of the week’ in your elementary textbooks makes written Japanese feel all the more daunting.

The downside to this approach, is that you don’t always learn the most useful, high frequency vocab until much later on. For example, using WaniKani’s system, you learn the word for testicles well before you learn verb ‘to hear.’

I’ll profess my ignorance here. I really don’t know which approach is better – in either the short- or long-term – or if some compromise between the methods needs to be made. Perhaps this will be the topic of a future post, once I’ve had a chance to take a look at the literature. At the moment I’m ambivalent.

Overall impression

All things considered, I really like WaniKani. Having completed the first 10 levels has made the world of kanji a little less daunting and helped in other areas of my Japanese study too.

While I realise that learning to read Japanese this early on is probably not the best use of my time, learning about another language’s writing system is a fascinating exercise in and of itself. What’s more, I’ve actually been able to stick with it. So, provided you’re getting a well-balanced study diet, WaniKani is a great way to get stuck in to Japanese vocab.

References

Nation, P. (2000). Learning vocabulary in lexical sets: Dangers and guidelines. TESOL journal, 9 (2), 6-10.

-

A made up example, but often not far off ↩︎