Review: Begat by David Crystal

Begat is an enjoyable, informative examination of the lasting linguistic influence of the King James Bible. David Crystal is someone who believes that this work alone has contributed more idioms to the English language than any other. His book fleshes out this theory.

The book is reasonably short, and, despite the lofty-sounding subject matter, makes for remarkably easy reading. I found it read much like a series of blog posts, each dealing with a selection of expressions and their usages since the 17th century. Some people find Crystal’s approach too formulaic, but I’d argue that he’s done a really nice job of making the topic approachable, even if the main premise is the somewhat dry, “let’s make a list of popular expressions from the King James Version (KJV) and see how people use them.”

Idioms and Quotations

In his introduction, Crystal clarifies what he’s really looking at. Namely, idiomatic uses of expressions from the KJV in modern English. To qualify for inclusion, these expressions need to be used by lots of people in a wide variety of contexts. Also, new, innovative uses should have evolved over time. Evidence of people simply quoting the KJV isn’t enough. In rough terms, this is the distinction he makes:

Quotation = verbatim text from the Bible, generally used only in religious contexts.

Idiom = an expression which has been adopted into the language and is used in non-biblical contexts, often adapted for rhetorical effect.

You might think that someone willing to write an entire book about idioms from the KJV would have at least a rough idea of how many are actually in common use. Not so. Now, understandably, Crystal is the kind of guy who can rattle off biblical idioms ad nauseum, but, as he confesses early on:

…if you pressed me on the point, and insisted on knowing how many there were in the King James Bible as a whole, I would not have been able to tell you. (pg. 2)

And it was this admission, and subsequent commitment to finding the hard numbers, that started to get me excited. Anyone can wax lyrical about how wonderful the KJV is and cherrypick examples of phrases in use today. But until you start doing some arithmetic, you aren’t able to say much more.

With that out of the way, Crystal gets into the nitty-gritty.

Of making many books there is no end

Broadly put, each chapter examines two things: 1) where a set of modern biblical idioms come from; 2) how they’re used today. The latter includes some spectacular (and spectacularly awful) puns, but it was the former that really grabbed my attention.

Although the KJV takes centre stage, Crystal regularly compares and contrasts this with other English translations of the Bible. The KJV certainly isn’t the only translation. Nor even the only one from Early Modern England. So it makes sense to compare it with other translations from the same period. As can be seen from the table below, several contemporaneous works are cited (Wycliffe being the exception).

| Translation | Year of publication |

|---|---|

| Wycliffe | 1388 |

| Tyndale | 1526-1530 |

| Coverdale’s Psalter | 1535 |

| Geneva | 1560 |

| Bishop’s | 1568 |

| Douai-Rheims | 1582/1609-10 |

Certain wordings are unique to the KJV, while others appear in one or more alternate translations. Unsurprisingly, the KJV phrasing often wins out (but this is not always the case). To see a typical comparison in practice, here’s an example comparing the expression “sufficient unto the day” between some of the texts (pg. 207).

| Version | Quotation |

|---|---|

| KJV | Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof |

| Wycliffe | it suffiseth to the day his own malice |

| Tyndale | the day present hath ever enough of his own trouble |

| Geneva | the day hath enough with his own grief |

Here, the KJV has a kind of punchiness to it. And perhaps more importantly, it lends itself to being shortened. A clear cut case of the KJV whomping it’s competition.

Quite honestly, I think these comparisons are fascinating. And, more importantly, they really strengthen Crystal’s case. Of course present day English includes idioms from the Bible. English-speaking countries have been predominantly Christian for hundreds of years. And of course the KJV played a huge part in entrenching these idioms. But what, exactly, is special about the language of the KJV? Throughout the book Crystal demonstrates just how the KJV differs from comparable texts, often positing stylistic features, such as rhythm and vocabulary choice, as the basis for the longevity of one phrasing over another.

What gets adopted and what doesn’t

Some biblical expressions make it into everyday language very quickly1, while other, seemingly productive expressions never do. To illustrate this, Crystal provides the following examples of idioms-that-never-were from Proverbs (pg. 97).

4:17 For they eat the bread of wickedness, and drink the wine of violence.

5:15 Drink waters out of thine own cistern, and running waters out of thine own well.

10:26 As vinegar to the teeth, and as smoke to the eyes, so is the sluggard to them that send him.

11:22 As a jewel of gold in a swine’s snout, so is a fair woman which is without discretion.

All of them are plausible additions to everyday speech - they’re descriptively striking; they’re well-suited to non-biblical contexts. But hey, they just got left behind. No doubt we could come up with reasons why these expressions never took on, but ultimately it seems difficult to ever really know.

Some phrases, however, become popular well after their appearance in the KJV. It’s noted that the expression Jesus wept! is a modern day expletive in the UK, Ireland and Australia, but that this usage seems only to date back to the twentieth century (pg. 250). Again, it’s hard to say why.

In addition, there’s a bunch of idioms we might reasonably expect to have originated in the KJV, but which actually come from other translations. In these cases the wording in the KJV sounds clunky (no doubt partly because it’s unfamiliar). For example, the phrase the scales fell from his eyes actually comes from the Wycliffe translation. On the other hand, the KJV plods along with “there fell from his eyes as if it had been scales” (pg. 201). Perhaps in these instances, the KJV still helped to popularize the expression, but English speakers used a more natural-sounding, paraphrased version. And this, coincidentally, closely matched an alternative translation.

A Book of Numbers

For me, the only thing that detracts from Begat is the occasional use of simple Google search results to quantify the prevalence of one usage over another, e.g. fire and brimstone over brimstone and fire (pg. 41). Sure, none of Crystal’s arguments rest on these search results, and he only seldom does this, but come on. Raw Google hits for a phrase? Even an undergraduate linguistics course wouldn’t let you get away with that!

Unfortunately for Crystal, Google Ngram Viewer wasn’t around at the time of writing (~2009), but both the British National Corpus and the the Corpus of Contemporary American English would have been. Referring to either of these would have lent authority to claims about frequency. A minor gripe, but still worth mentioning.

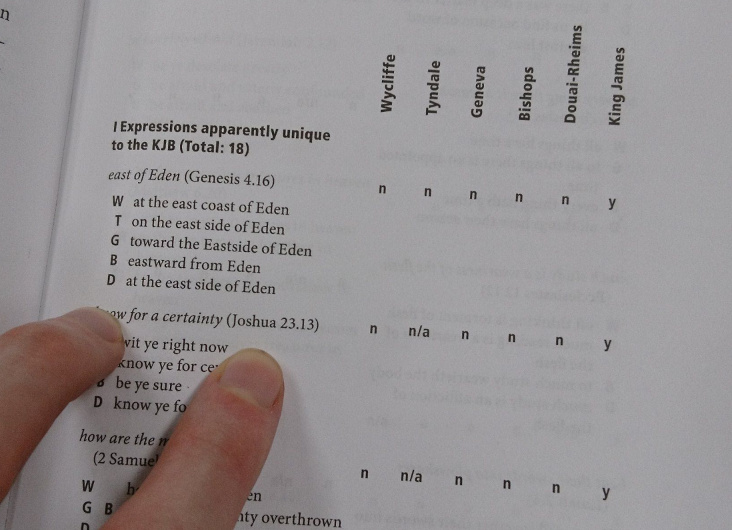

By contrast, when Crystal goes into the numbers with his source texts, he’s more than thorough; he’s meticulous. And this culminates in the glorious table in the appendix. Hard counts are given for everything.

The beginning of the quite wonderful appendix.

The beginning of the quite wonderful appendix.

Appendix 1 contains a table of all expressions discussed in the book. The table is divided into 10 sections:

- Section 1: expressions from the KJV which are not present in other translations.

- Sections 2-6: expressions whose phrasing appears in one or more of the other translations.

- Section 7: modern variations of expressions which do not match any one translation.

- Section 8: expressions which are not in the KJV, but are in one other translation.

- Section 9: expressions which occur in the KJV and Coverdale’s Psalter.

- Section 10: expressions from the KJV which already had a history in Old/Middle English.

Seriously, this table is the business. It turns what easily could have been a quaint discussion of the KJV into a serious reference work. Big fan of this and it was a nice note to end on.

Conclusion

I’ll admit that the sceptic in me had assumed Crystal would go a little too far in this book, that he’d overstate the importance of the KJV and make claims that overstepped the evidence. But what I found instead was a very measured discussion. This passage from the Epilogue, gives a feel for his nuanced position:

We must immediately curb our enthusiasm, therefore, by reflecting on the facts summarized in this Epilogue. Very few idiomatic expressions unquestionably originate in the language of the King James Bible. An entire biblical era, of over a century, lies behind them. There can be little doubt that this ‘authorized’ version translation did more than any other to fix these expressions in the mind of the English speaking public. But the myriad contributions of Wycliffe, Tyndale, and many others also need to be remembered… (pg. 262)

No grandiose claims here. The KJV is unquestionably important, but so is the historical context which led to its creation.

Ultimately though, Crystal stands by his assertion that the KJV is the single most influential literary work in English, at least in terms of its impact on the language’s idioms. It may not be as unique as is often thought, but it’s unique contributions dwarf those of any other work. And, staring at the appendix, that seems pretty hard to refute.

Overall, Begat exceeded my expectations in ways I didn’t expect. I was certainly prepared to enjoy the book, and gobble up the tidbits I considered “Superb cocktail party fodder."2 But Crystal, in a very unassuming way, gave me a great deal more than I’d hoped for.

It’s well worth a read, so please: Go, and do thou likewise.

Reference

Crystal, D. (2010). Begat: The King James Bible and the English Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

-

One example being no small stir, a uniquely King James phrasing, which is first recorded in non-biblical contexts as early as 1670 (see pg. 159 for details). ↩︎

-

A hope expressed in my 2019 reading list. Although, strictly speaking, I don’t think I’ve ever been to a cocktail party, least of all one where the subject of conversation is Early Modern English biblical translation. A man can dream though. ↩︎